Points of view

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

|

What should a pub menu look like?

If you are a regular reader of these newsletters, you will be aware that I have not aways been terribly impressed by the quality of pub food – particularly recently. This dissatisfaction raises a number of questions:

· Why is pub food so poor? · Does it have to be this way? · Is there a shortage of chefs (with the right skills)? · For chains, does central purchasing dub down the quality? · Has the recent rise in food prices affected the quality? · Is there something in the way that food is prepared for public consumption inevitable mean that the quality of the food will be poor?

I am not going to attempt to answer these questions here; there will be heaps of opportunity for that in the future. I am going to answer another question, “What should a pub menu look like?” Before doing that, let me make a couple of observations:

· The first is that pub food is better in some parts of the country than others. · Some pubs do produce really very good food.

So, what should a pub menu look like? Here some things I look for:

1. The food should heathy (a test of this is to go on a weight-loosing diet and ask yourself if the food is going to help you with that diet. 2. The food should be fresh, in season and locally-sourced.

Here is my version:

Please note that there is no Lasagna. Lasagna is ofter referred to as a “tradional pub” dish. Why? Presumably because it was introduced by the Romans when they invaded in 43AD and has been served in pubs ever since.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Drink to save the planet

You have probably and thankfully forgotten about COP26 but the December edition of Decander Magazine jumped on the climate change bandwagon and published an article about wine production and climate change.

The article recognised that producing and distributing wine will produce climate change gases; it suggested that the amount was “significant” (really, compared with producing a Tesla car?); it anticipated that some wine producers could become carbon neutral (not sure how?); but it proposed that wine consumers should be climate aware when buying and drinking wine. It suggested a number of ways that consumers can help. These included:

The thing that is missing from these ideas is the quality and indiividuality of the wine. Basically most of these suggestions say “Buy rubbish wines”!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What has happened to pubs and restaurants? I have written about pubs in the past and what they think they are. I have praised some pubs and made strong recommendations that reflect the quality of the service they have offered. Over recent weeks I have become extremely disillusioned and shocked by the state of pubs in this country. I shall present some of my complaints below, but first let me explain why how my experiences have come about. Firstly we tend to visit a pub with a Ramblers’ walk. This lets me see quite a few different pubs. Secondly, we have just had a week-long holiday near Rye in Sussex. On arriving in Rye we spend about 2 hours trying to book tables for dinner for each of the next seven nights. We managed to book one for three nights but not the other four. This was essentially because restaurants were working below full capacity mainly as a result of staff shortages but also, possibly, because they were still operating so-called “social distancing”. That is restaurants, so what about pubs? We have eaten in some recently. We have tried, unsuccessfully to eat in others but the following sums up our experiences:

Pubs have obviously suffered enormously as a result of the government’s response to Covid, but they have had some benefit from the numbers of people staying in this country rather than going abroad for their holidays. That said, if they want to get back to their former position in the hospitality sector, they are going to have to raise the bar on the service they provide. Returning to restaurants (and, no, I do not regard McDonalds as being restaurants), I observe that, particularly in rural areas in this country, there is a significant shortage of restaurants – partiularly compared with other places where I have been on holiday. I suspect this could act as a significant barrier to the growth and development of the UK tourist sector. The question is what to do about it? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What is a restaurant?

The government, as part of its (unsuccessful) measures to control the China virus, introduced a range of regulations affecting what it called “restaurants”.

The use of this single term, restaurant, applied to a range of establishments from take-away food suppliers to haute cuisine restaurants (see below).

The point I wish to make is not about the regulations, but about the nomenclature of the establishments. They are quite different from each other and the nomenclature used leads potential customers to expectations of quality and price. You would not be expected to take your spouse to a soup kitchen to celebrate 39 years of marriage – a restaurant might be more appropriate. That said, although we in the UK expect railway buffets to serve curled up sandwiches and similar delights, the railway buffet in Arras in Northern France used to have a Michelin star and people used to travel from miles away to eat there!

What I am trying to say is that MacDonalds does not have restaurants.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Supply chains

After the collapse of the USSR, John Major lent Boris Yeltsin a team of top supply chain experts to help Russia build up its supply chain infrastructure, post-USSR. I remember thinking at the time, that our own supply chains were not that good and should we really be advising other countries how to do it? Notwithstanding panic buying, the Chinese virus has highlighted a number of shortcomings I felt about supply chains back in 1990’s.

1. Our supply chains are not robust enough to withstand upward fluctuations in demand. Yes, there were shortages of products where there was panic buying, but these shortages continue even now. Some of the shortages even applied to essential goods such as milk and flour.

2. There are separate supply chains for different end-buyer sectors (particularly, retail and hospitality) with the result that there can be shortages in the shops at the same time as surpluses for the same products elsewhere in the market. Thus, we saw milk shortages in the supermarkets at the same time as farmers were pouring milk down the drains. Similarly, there were flour shortages in the supermarkets at the same time as many millers were unable to sell their flour.

These separate supply chains also meant that, as the hospitality sector was shut down, a number of producers were unable to sell their goods. A glaring example of these was cheese makers (more milk down the drain) and now there is a shortage of some cheeses.

Incidentally, the separation of supply chains is equally well established in the drinks sector. Very few wine merchants sell to both the off-sector and on-sector and, if they do, it is either through separate subsidiaries or they sell different products. One thing restauranteurs hate is to see a wine they sell for £30 being sold in a supermarket down the road for £10!

3. Another thing the Chinese virus has highlighted is our dependency on produce from overseas. My views on Peruvian asparagus, New Zealand apples and Greek farmed fish are well documented but the virus threw up another import dependency that I could not imagine. After getting over the flour shortages, bakers found they could not make bread because of a shortage of yeast – yes, yeast! We have a net trade deficit of yeast of about £100 M. Surely, we can make our own yeast? And from where does it come? The three largest exporters are: France, Turkey and China!

Apart from waste and shortages, are there any other negative implications of our supply chains set up? Probably the most significant one for me, as a Francophile gastronome, is the number of produce that are hard to find – not because there is a fundamental shortage but simply because our supply chains do not cater for the less usual. I made a list of some of these:

Food

I am sure you will agree that these are all essential items!

Drink

So, what is to be done about this? To mix clichés, we need a three-point road map…

1. Much greater encouragement for local production and supply. 2. A more enlightened approach to food hygiene regulation. 3. A full enquiry into the food supply chains from farm to plate.

As a final comment, it must be said that many of the comments above not only apply to food and drink, but also to other goods, such as white goods. The virus has led to a shortage of freezers! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

How much should you spend on a bottle of wine?

Here are a few observations.

1. The duty on a bottle of still wine and the VAT on the duty (yes, we really do pay tax on tax!) come to £2.68. At the average price of a bottle of wine sold in the UK of £5.68, £3 covers the wine, packaging, transport, marketing, etc. The cost of the wine is 53p. For any bottle costing less than the average, the value of the wine will be even less. What this says is that there is a level at which the wine is bound to be of very poor quality. In fact it is almost certain to be of poor quality; however, it must be acknowledged there are wines that are good even at these levels. 2. Some people say you should buy the most expensive wines you can afford. I think that this is not necessarily the case. 3. Does the quality of the wine go up in proportion to the price? Certainly at the lower end (say, below £10 per bottle), for reasons given above, there is a reasonable correlation between price and quality. At the top end I state that you can get a “perfect” wine at £500 but, unfortunately, my experience does not extend to £22,000 per bottle. At this level, the price is possibly more to do with the balance of supply and demand rather than quality. 4. Wines from some appellations will always be more expensive than others simply because of the landscape and conditions needed to produce the wine (eg where botrytis is necessary) 5. As a general rule, spending between £15 and £20 per bottle should give you a good and enjoyable bottle of wine. Going up to £45 should give an excellent bottle even from more expensive appellations such as Côte Rôtie and Condrieu.

When looking for Loire wines for the next dinner, I was quite surprised by some things that I found. Firstly, it must be stated that Loire wines are generally modestly priced and it is not difficult to find very good wines in the £15 to £20 price bracket. The second thing to say is that La Loire has some appellations that are unique, rare and quite delicious. One of these is Savennières in Anjou. It is a dry wine made from the Chenin grape. It has great complexity and the ability to age for ever. It is rare but can cost between £15 and £20 per bottle. Equally, lurking amongst wines normally costing between £15 and £20 there are wines costing hundreds of pounds.

My advice is to choose the wine that does the job you want (for example, a Muscadet with shell fish) irrespective of how cheap it is. If it works for the occasion then that is good.

As a footnote, it must be stated that prices quoted above are for still wines. You must expect to pay more for sparkling wines but the arguments still hold.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“Dessert” wines?

Christmas got me thinking about sweet wines.

How often do you see sweet wines being referred to as “Dessert wines”? If you ask any (French) producer of sweet wines when you should drink them, they always give the same answer…

1 With foie gras 2 As an apéritif, and lastly 3 With dessert.

There are three reasons why it is incorrect to refer to sweet wines as being “dessert wines”:

1 Because they are only drunk with desserts as a last resort, and 2 As we have found during a couple of our dinners this year, a dry wine or a sparkling wine can go extremely well with sweet desserts, 3 Sweet wines also are particularly well paired with (some) cheeses – particularly blue cheeses.

That said, when trying to match sweet wines with desserts, I have been frustrated by how few sweet wines are available and at having to resort to the same old favourites of Monbazillac and Muscat de Beaumes de Venise.

To make three comments about sweet wines:

1 They will never be cheap and, if they are, you should be suspicious. They sometimes require multiple passes through the vineyard to pick the grapes at the optimal time. They sometimes require the grapes to be sun-dried to concentrate the flavours. 2 The grapes used to produce some of the best will have been affected by botrytis or “noble rot”, a mould that concentrates the grape juice. Botrytis only occurs in a few locations and then only when weather conditions are absolutely right. Botrytis affected wines are therefore rare and expensive. 3 Sweet wines are not only made by the natural, but incomplete, fermentation of grape juice leaving residual sugar, but they are also made by fortifying wine (adding alcohol to stop the fermentation) and by adding alcohol to unfermented grape juice.

Whilst I fully recognise that sweet wines are produced in many parts of the wine-producing world, below is a list of some from France and the Iberian Peninsula.

There is a particularly rich choice of sweet wines, some of which are well matched to (some) foods and some of which are stunning by themselves. They cannot be cheap, but the good news is that they keep for a reasonable length of time when opened.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Whence does our food come?

In the 1990’s, after the fall of the iron curtain, John Major sent a special task force to Russia to advise them on setting up their food supply chains. I remember thinking at the time, “What the hell? What do we know about it? Our supply chains are dominated by the supermarkets and are hardly doing great service to food consumers or producers. Perhaps we are trying to sabotage Russia’s food supplies and to get them to submit to Western ways through starvation.”

I would note here that the same sort of supply chains is now working for small independent food shops as work for supermarkets – with a few large dominant wholesalers.

What brings that task force back to mind now is that a week or so ago I discovered that we were buying Braeburn apples from New Zealand! “What is wrong with that?” I hear you say. Well three things.

1. It is the peak of the English apple harvest so why do we need to import apples from the other side of the World? Should we not be supporting English farmers? 2. These New Zealand apples were harvested 6 months ago. Would it not be better to be eating fresh apples? 3. Is it right to be polluting the atmosphere by shipping these apples from as far away as it is possible to get?

Those Braeburn apples came from a well-known supermarket but it is not just the supermarkets that are guilty of these practices. Last week I found a local greengrocer selling South African apples. Same issues: transport from the southern hemisphere and harvested 6 months ago.

Another example of shipping across the world when we produce the product locally is garlic. Do we really need to import garlic from China when there is a local producer as close as the Isle of Wight? If they have run out, then there are ample supplies of garlic much closer than China in France, Italy and Spain.

Then there is fish! We buy farmed sea bass from Greece. In Greece they buy their fish from Italy!

There are many other examples for such outrageous behaviour. Perhaps Extinction Rebellion should concentrate their efforts on stopping this unnecessary transportation of food.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Are wine medals a useful guide for the consumer? In the past, I have

ranted on about wine “challenges” (that is wine competitions), and

whether their results (medals awarded to wines) are a useful purchasing

guide for consumers to find good wines. I have argued that these wine

events are seriously flawed and that the results are of little value as

a guide to which wines are good. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

English products

On being invited recently to a St George’s day dinner, our host suggested that we take something English (made in England) to go with coffee. He might as well have asked us to take moon rock!

Our thoughts went to chocolates and biscuits and so we went on a mission round Romsey to find English-made chocolates or biscuits. Admittedly, we did not venture into the Forest to find some of the excellent hand-made chocolates that are made there, but the results were not good.

We did venture into Romsey’s supermarkets, 2 of Romsey’s delicatessens, a sweet shop and even a charity shop that sells biscuits and chocolates. The result:

· NONE of the shops sold English-made chocolates. · In one shop we were directed to some shelves and told, “All those are made in Kent.” Good news except careful examination of the packets showed that the company’s registered office was in Kent, that the goodies were packaged in Kent but they were made in France. · It became apparent that the first clue that a product was not made in England was the presence of Dutch writing on the packet. · Eventually we did find something that was made in England in a supermarket. That, however, was so uninteresting that I cannot remember what it is.

All this raises some important questions:

· Why is there an almost complete absence of English-made interesting biscuits and chocolates in our shops? · What can be done about it? · Why do some producers go to such great lengths to give the impression that their products are made in England when they are not? |

Made in

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Globalisation v’s artisan

It is quite gratifying when people respond to my comments in these newsletters. A very knowledgeable gentleman responded to the bit about Cheddar cheese, by writing about the global market for cheese. He also suggested that the days of cloth wrapped Cheddar are numbered.

This got me thinking about whether there is a battle between globalisation and artisan producers. It should, perhaps, better be described as a battle between mass- and artisan production. It is a battle affecting many types of produce including wine, beer, gin, food stuffs, perfumes, cloths and even cars. Rather than a battle it is more an ebb and flow between mass-production and artisan. Mass production and globalisation grow and then suddenly there is an influx of artisan producers. These grow; the most successful ones get taken over by the global players and so on.

Although any of the industries listed above could be used to illustrate the market development described, the UK beer market is very typical.

Up to the 1930’s there were 2000 breweries in the UK - many of them local. Over the next 30 or 40 years “rationalisation” took place and many of the breweries were taken over by the national companies and by global players. Then there was an upsurge of new independent small breweries – a growth of 64% in the last 5 years alone. In spite of this upsurge, some of the small breweries continue to be taken-over or to close. For example, Fullers beer is going to a global Japanese firm.

What drives a market to globalisation (mass production) or artisan production?

To globalisation: · Corporate needs for growth · Corporate desires for cost reduction and profitability · Dominance of large retailers (supermarkets) · Most consumers in the UK do not care about the food they eat and the drink they consume so long as it is cheep and readily available. This plays to mass production and globalisation.

To artisan production: · Some consumer rebellion against globalisation · Some consumer desire for quality and diversity · Limited potential production. For example, the Romanée-Conti vineyard is so small that only about 5000 bottles of Romanée-Conti wine can be produced per year.

Other market influences: · Taxation – there is an intriguing development in the UK beer market. Small producers (producing less than 5000 hl) pay 50% less duty than larger producers. As a result, some small brewers, when they grow to more than 5000 hl, set up a second company to keep below 5000 hl and to continue benefitting from the lower duty rate.

Does it matter if a product is global or artisan? The table to the right shows there are advantages and disadvantages of each. Which one any individual prefers depends on personal taste. The question is: how much influence do consumers have?

The final point of interest is that artisan production has been vigorously supported by the Slow Food Movement. This was started in Italy in response to MacDonald’s opening a “restaurant” near the Spanish Steps in Rome. Its aim was and is to promote local foods and traditional gastronomy and food production. Conversely, this means the opposition to fast food, industrial food production and globalization.

The Irony

The irony is that The Slow Food Movement is now global with offices in Italy (HQ), UK, USA, Chile, Switzerland, Germany, France and Japan.

|

Advantages and disadvantages of global products v’s artisan product

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rind, protection and bureaucracy

This is a tale of rind, protection and bureaucracy or it could better be described as no rind, no protection and gutless bureaucracy.

Last month our oxymoron of the month was “Welsh Cheddar”.

Cheddar originated from the village of Cheddar in Somerset although there is only one producer based in Cheddar. It is the most popular cheese in the UK, accounting for 51% of the UK cheese market and the second most popular in the USA. It can be absolutely exquisite but it can also be rubbish. The trouble is that it is produced in a number of different places far from its origins and with no laid down standards. Basically, any hard, yellowish cheese may be called Cheddar.

Does that matter? If the consumer needs to know what he is buying, then it does matter.

I believe it would be beneficial to give Cheddar a level of protected status; after all, some 11 British cheeses have either Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) or Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status including Stilton, Dorset Blue Vinney, Swaledale and Staffordshire.

What could be included in the specification for protected status? How about:

· Origin of the milk · What kind of milk - cow · Where the cheese is matured · How it is made – use of rennet, cloth wrapping (producing a rind) · Time of maturing

Any cheese that does not conform to the specification should not be allowed to use the name “Cheddar”.

Now we come to the tricky parts of the story…

· There are, in fact, protected designations for two types of Cheddar. West Country Farmhouse Cheddar (PDO status) which must come from Somerset, Dorset, Devon or Cornwall and must be made to certain standards. There appears to only be one company make cheese to that designation and they were the ones who applied for the designation. The second is Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar (PGI status). · It must be recognised that there are excellent producers of Cheddar that are nowhere near Cheddar, The Mendips or even Somerset. · There are organisations selling “Goats milk Cheddar). Whatever your views on protected status, that cannot be right. Worse than that… ”vegan Cheddar”! · Origin needs some care. Wookey Hole is made from milk from Dorset but the cheese is matured in Wookey Hole a cave in the Mendips near to Cheddar.

The question is why have the authorities not taken a more robust approach to protecting the Cheddar name. The reason is probably that there are so many powerful producers and retailers of “Cheddar” that bears little or no resemblance to traditional Cheddar who want to protect their brand, that the authorities will not face them down.

|

A Quickes Cheddar truckle. As good a Cheddar as you will find but from Devon – not Cheddar

An American version of “Cheddar” Can you spot the difference?

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oxymoron of the year

Last month our “Oxymoron of the month” featured non-alcoholic wine. Already this year we have an even more impressive one, “Non-alcoholic gin!”

This is particularly oxymoronic (apparently that word exists) because it does not align with the legal definition of gin…

In the EU, the minimum bottled alcoholic strength for gin, distilled gin, and London gin is 37.5 per cent ABV and that it must possesses the characteristic flavour of juniper berries.

Curiously, in the USA, gin must be 40 per cent ABV. Perhaps after Brexit we can adopt the US, less watered-down definition.

Anyway, a drink with no alcohol cannot be gin. To give them their dues, the producers and retailers do not call them “gin.” Instead they refer to it as “non-alcoholic spirits.” That, however, does not get them off the hook because a spirit is an alcoholic drink of more than 20 per cent ABV!

I would not dream of suggesting that there is something fraudulent about these products but…

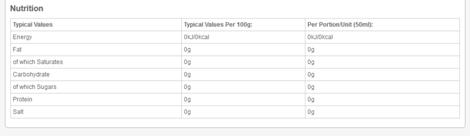

· The costs of these drinks are outrageous – about £20 for 50cl. This must put them amongst the most expensive non-alcoholic drinks. OK, a bit cheaper than Ruwa which retails at £3.4m a bottle – but you do get a load of diamonds with it. · They do not seem to contain anything. See the nutritional chart below for one of the products. Sorry it is not very clear, but they obviously do not want this information to get out. If you cannot read it, all the numbers are ZERO.

· Below is a snapshot from one supermarket web site. How does this work?

If you are driving and do not want to drink but you are desperate for a gin and tonic them ask for “A gin and tonic without the gin.” If you want gin flavour, you can always drop a few bits of juniper berry into it – I am sure you always carry a packet of juniper berries in your pocket or handbag.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Christmas food

Big turkey crisis!

For the past 30 years or so we have bought our Christmas turkey from the same farm. We would ring up a few weeks before Christmas to place our order and turn up a day or two before Christmas to collect the order. Everything was easy and straight forward. We could even take great satisfaction from the knowledge we would not have to queue round the block to collect a turkey from a butcher or join the scrum at the supermarket. One further thing about our turkey; I like to buy it long legged (feathers off, guts in) so that I can prepare it the way I want.

This year, we rang the farm as usual but were told, much to our dismay, that they are not doing poultry this year.

Off we go, then, to find a turkey. Where do we start. Throughout the year, we have noticed signs outside various farms saying, “Free range turkeys for sale.” Now we need to buy a turkey, they all seem to have disappeared. I am pleased to report that we have now found what appears to be a suitable one but I have learnt a few things on the way. 1. There are essentially two types of turkey: white ones and bronze ones. The white ones are fast growing, round in shape, cheaper but have less flavour. Bronze turkeys are slower growing, have more pointed breasts, have more flavour but are more expensive. The cheaper supermarket turkeys tend to be white turkeys – the clue is that they do not tell you what sort of turkey they are. 2. Turkeys are either free-range or barn-grown. The free-range turkeys have a more natural environment. 3. Prices vary significantly 4. Turkeys are game birds and should be hung before they are consumed.

I would like to thank various friends and acquaintances that helped us track down a turkey. It really helps to know people in the farming industry!

If you cannot find a turkey, then there is always lame duck!

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Frying oil

When I took up bee keeping, the first thing I learnt was that, if you ask two bee keepers for a piece of advice, you get at least three different answers! Not only that, but the bees have their own ideas and will do something completely different.

It seems that cooking is similar to the first part – about getting three bits of advice from two people.

I needed to answer the question, “What type of oil for frying?” So I asked people for advice and got quite a lot of conflicting responses. So I did some research on the Internet. Lots of conflicting answers and, even with “scientific” information, I am now completely at sea.

What I have gained is some insight into what are the important selection criteria for selecting the oil you use. These are:

1. The Smoke Point of the oil. This is the temperature at which the oil breaks down. It is related to different types of fat in the oil (Saturated, Monosaturated and Polyunsaturated). The Smoke Point needs to be as high as possible because low Smoke Point oils break down to produce nasties (not sure what or what they do to you). Oils with higher levels of Saturated fats tend to have high Smoke Points, BUT… 2. Health qualities of the oil. Oils with higher levels of Saturated fats are not good for you. 3. Flavour. Generally, but not always, frying is best done in oils that do not impart flavour to the food being fried. 4. Colour. It is probably desirable that the oil does not colour the food being fried. 5. Clinginess. An oil that does not stick to the food would be healthiest. 6. Environmental impact. Palm oil harvesting is meant to be really bad for orangutans so, if you care for them, do not use palm oil. 7. Cost. As is usually the case, the more expensive, the more likely the oil will be less bad for you! However, would you fry in a top Extra Virgin olive oil costing £50 per litre?

The state nannies would say, “Do not fry – it makes you fat.” or “Do you want to die of a heart event or cancer?” The UN would say, “Do not fry – it makes the food carcinogenic.” The question is, “what are the risks?”. Frying is a traditional and well-established way of cooking food which can produce wonderful results. Unfortunately it can be overdone.

What oil do I use?

1. I shallow-fry in extra virgin olive oil. It is not cheap and it does impart some flavour to the food, which I like, and it is healthy. 2. Goose fat is excellent. It is healthy but it does flavour the food, which can be a huge benefit. Potatoes, in particular, are excellent fried in goose fat. It is not cheap. Best to start with a whole goose, roast it and collect the fat. 3. When I do not want any oil flavours in the food, for example with a meat fondue, I use groundnut oil. This oil is comparatively healthy and has a high Smoke point. 4. I do not deep-fry very often but, when I do, I use corn oil which has a low percentage of saturated fats and a high Smoke Point.

Finally, do not believe anything you read about oils!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Apéritifs Apéros Aperitivi Aperitivos απεριτίφ

We were about to have dinner in a local restaurant and thought that an apéritif would be a good idea. We were given an extensive and impressive menu of gin and tonics. This completely confused me and, although I like gin and tonic, I could not decide what to drink. At the time I was not sure why but it did get me thinking about apéritifs.

Apéritif is a French word derived from the Latin verb aperire, which means "to open". Although we tend to think of apéritifs as “something to do while we decide what to eat and while we wait for our order to be taken”, they do have two important roles. The first is to stimulate the appetite and taste buds and the second is to get the party going.

With that in mind, what are the best and worst drinks to have as an apéritif and what drinks are not suitable? Apéritifs can be sweet or dry, although in this country they tend to be on the drier side. They can be wine-strength or fortified wine-strength. What should be avoided are spirits – hence my problem with the gin and tonic menu!

At the end of the day, it depends on what you like, and whether you think the food that is going to follow is worth tasting.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Champagne grower-producers

I have just been reading in the August edition of Decanter Magazine (no, that is not an error – it came out in June!), about the demise of grower-producers in Champagne. These are people who grow their own grapes and make their own Champagne. The argument of the article is that, although there are currently over 4000 grower–producers, the number is falling and eventually there will not be any.

In the piece, a number of individuals in Champagne are quoted, but these mostly seem to have interests in the big houses, so they would say the days of the grower–producer are numbered, wouldn’t they? Whether or not the number is decreasing and whether or not the trend will continue it is worth considering the reasons given for this and to consider whether or not it matters.

1. The price of grapes in Champagne is so high that a grower can make a living without having to go to the inconvenience of making and selling his own wine. Perhaps, but what happens if the big players start to behave like the supermarkets and reduce the price they will pay. 2. In the export markets, the price of Champagne is so sensitive that the small producers cannot compete. The evidence given for this is the cost cutting and “special offers” from the supermarkets. Two comments: (1) the supermarkets generally sell grande marque champagnes and these probably start at 30% more than an equivalent grower Champagne so the sensitivity only comes after the prices have been bumped up and (2) there is at least anecdotal evidence that people will buy a more expensive brand and buy on price alone. 3. Big houses can hold reserve stocks and blend to produce consistency. The quality of wines from small grower–producers is more dependent on the weather. This issue of blending for consistency is at the crux of the difference between the grande marque houses and the grower-producer. Is it better to have a consistent house style year in year out or to produce a wine that reflects the season and the terroir? 4. French inheritance laws, which require an equal distribution of inheritance assets between siblings, coupled with 45% inheritance tax on assets worth more than €1.8M. With the average value of a Champagne vineyard being a staggering €1.8M per hectare it is not surprising that grower-producer businesses are being sold-off and broken-up. 5. Small grower-producers are more at risk from weather events than the larger houses. This sounds logical, but it equally applies to growers who sell their grapes to others to make the wine.

Assuming that this decline in the number of grower-producers is happening and is going to continue, does it matter? I think it does for three reasons:

1. Grower-producers make Champagne that is more artisan and individual than the grande marque houses – often expressing terroir better. 2. Grower-producer Champagnes are often better value for money than grande marque Champagne (because they do not spend so much on marketing). 3. Most importantly, if there were no grower-producers, virtually all Champagne would be sold through supermarkets, resulting in a concentration of the retail market and even less choice.

What can we do about it? When buying Champagne, look for the “RM” (récoltant-manipulative) designation on bottles (usually in very small letters) as opposed to “NM” (négociant-manipulative).

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Why is pub food so unhealthy?

I have a big problem. By 10th August I have to lose 1½ stone (or, more accurately, I have to lose 4 inches from my waist) and, because we have been going on Ramblers walks regularly, I have been eating a fair number of pub lunches. Unfortunately, most pub food is extremely unhealthy and cause you to put on all the weight taken off on the walk. The simplest way to sum up most pub food is double carbohydrate. Typical of this formula is:

Batter AND Chips Pastry (pie) AND Potato Potatoes AND Bread Pasta (always lasagne) AND Bread or chips

Whilst, I would not wish to deprive chip addicts of their daily fix, I do think that pubs should offer healthy options. They might do quite well!

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Labels

A week or so ago a shopper at a farm shop was being interviewed…

Interviewer: “Do you try to eat healthily?” Shopper: “Yes, I always read the label before I buy.”

There are two issues relating to this short exchange.

The healthiest food is unprocessed and does not come with a label. Does labelling help that much in guiding us to the most healthy food?

Some people have great faith in the power of labelling. The question is whether it helps that much.

Labelling has several objectives:

1 To inform the consumer about the product – specifically about the ingredients of the product, it’s energy value, etc. These are meant to help with making healthy choices. The problems are: understanding what the values mean, making a choice involving a number of different measures (is it better to have more sugar and less salt or vice versa?), knowing what the different chemicals and E-numbers mean or do to you and, oh yes, being able to read, what is sometimes, very small print. Also, not all products show this information – including processed food.

2 To provide warnings about allergies. There are two problems here relating to wine and drink. Firstly, for all practical purposes it can be assumed that all wines contain sulphur but it has to be listed as something that might cause allergies. Almost no one is allergic to sulphur (although some people will say it causes headaches – could not possibly be the alcohol(!)). Secondly, some wines (and beers) do contain things that do cause an allergic reaction. My mother could not drink Burgundy, I have trouble with expensive Italian red wines beginning with “B”. There is something in a particular Cairanne that gives me a headache (see below). No warning on the bottle!

3 To provide the supply chain and authorities with an “audit” of the production. For example, in the Cairanne which gives me a headache, the label says “mis en bouteille par F71084A pour J. Boulard 71570 France”. Presumably someone in authority knows who or what F71084A is but not even Google will enlighten the consumer.

4 To advise the consumer about the life of a product. The problem here is whether a date on the label is meaningful. I could write about chutney and the random rules about setting “use-by” dates on jars of chutney. Instead here is a glimpse of bureaucratic randomness. The local trading standards people came into Heaton Wines and started inspecting sell-by dates. None on wine, but that is ok. Some on UK-produced cider. All in date, so ok. No date on Normandy cider. “Cider has to have a sell-by date,” they said. “Not Normandy cider,” I said. They went away.

5 To brand the product. The problem here is that people change the brands. Some time ago I wrote about a bottle of Cairanne bought from Waitrose. Last week, I bought what I thought was a different Cairanne also from Waitrose. In fact, it was the same; just the label was different. Still contained the same headache – nothing on the label warning about that.

In conclusion, buy food that has no label; when buying wine do not pay too much attention to the label. Oh, there is a sixth objective of labelling: “To fuel state bureaucracy”

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When is something in season?

February is a tricky month for acquiring (1) fresh, (2) local and (3) in-season fruit and vegetables. The shops appear to be full of produce that meet some of these three categories – but very few that meet all of them. Where they do meet them all, it is usually found that the season is being stretched by use of greenhouses and variety selection and that the produce has no flavour (you can buy local, fresh tomatoes but they do not taste of anything).

Some years ago “The World’s Favourite Airline”(!!!), served me dinner on the way back from Rome to London. The dessert, according to the menu card, was “Seasonal Fresh Fruit”. It consisted of: half a strawberry with the green bit left on (I hate that), a couple of grapes and a slice of melon. Apart from the dish being inadequate by any standard, I was compelled to ask the steward which season was represented by these samples of fruit. The answer was that “the whole world has one season” and everything is in season. I would say that different parts of the world have different seasons at any one time. I would also say that “seasonal fresh fruit” implies that all the fruit comes from one season rather than anywhere in the World.

Whilst some… many… most foods have distinct seasons some do not and are freshly available all the year round. Examples of this are beef, pork, mutton and most fish. Others are much more restricted. Examples are fruit, vegetables and specific types of lamb.

One further observation, watch the marketing. We recently (in January) came across “Jersey Royals” – in January? – and “New season’s beetroot”. We have been harvesting beetroot since August. How can January be “new season” for beetroot?

On a happy thought, looking forward to English asparagus. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When is a pub not a pub?

We have been doing a bit of walking with Romsey Ramblers and these walks inevitably take us to pubs for lunch. This is giving us a wider perspective of the pub population than we have had before and what we observe is that many pubs are no longer looking or feeling like pubs. They are often like sad representations of restaurants. That said, there are some pubs that are traditional, welcoming but still manage to offer good food at reasonable prices – indeed there are some pubs from which I have had great difficulty in prising myself in order to complete the walk! The question is how can you identify the good ones? Perhaps the following might help.

The trouble is that more and more pubs are trying to behave like the right-hand column and, sadly, they are not very good at it. Without naming any culprits, I can think of one New Forest pub that describes itself (on its website) as a family run, unspoilt, traditional 18th Century Country Pub. I cannot argue about the 18th century. It may be family run but it appears to be in a group with other pubs. What I do take issue with is the “unspoilt traditional”. On the other hand, I can think of a pub just outside Lymington that, as soon as you walk in, it wraps you in a traditional pub atmosphere – and they still manage to do cracking good food.

One other criticism of the New Forest pub cited above is on their menu. In the section headed, “OLD ENGLISH CLASSICS”, appears, “Baked Tandoori Chicken Breast with Saffron Quinoa, Homemade Chapati and Onion Bhaji”. Nooooooooooooooo!

Finally, as it is the new year, I thought I would name the best pub we visited in 2017. By a short whisker, the winner is: The Talbot Inn in Berwick St. John. I had great trouble leaving that one.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Does breed matter?

I keep having a discussion with a friend about whether breed of animal matters when it comes to the flavour of the meat. My friend argues that it is the food the animal is fed (he used to work for an animal feed company), the husbandry of the animal and the butchery, including the length of time and way that the meat is hung, that matter the most. I have even heard a butcher arguing the same when he had run out of South Devon beef and was trying to sell us something else.

Although I have not tasted very many beef varieties, my experience is that I have noticed a significant difference and improvement of taste with some varieties. I would cite South Devon, Hereford and Longhorn as being particularly tasty. All you have to do is show a steak from these animals to a griddle to get an alluring and enticing aroma not given off by most steaks on offer in the shops.

One of the most common “premium” beef variety is Aberdeen Angus. It is all right but, if you compare an Aberdeen Angus steak with a Longhorn or a South Devon steak, there is no comparison.

The difference in flavour between breeds is perhaps more striking for lamb than it is for beef. Compare a Soay (almost venison-like meat) with a Dorset Pole (sweet and juicy) and the difference could not be greater. I mention this to support my assertion about beef.

It also applies to pork. Compare a Gloucester Old Spot with the pink jobs most butchers sell.

Assuming, then, that my assertion about the effect of variety of taste is correct, the question, then, is what should or can we do about it? Here are two responses to this question…

1. Take the effort to seek out suppliers of better varieties of meat. Some farm shops do specialise in better varieties. 2. Always to ask the butcher, farmer or restaurant from what breed of animal the meat comes. Some will know the answer and will be pleased to tell you, others will not have a clue. If enough people ask, then perhaps they might do more to source their meat from flavoursome animals.

Here are some additional comments:

· Many (most?) breeds of animal are bred for commercial gain rather than flavour. · The comments about breed also apply to poultry (how often do you see the breed of a chicken on the label?), game and even vegetables which is one reason why people have allotments! · We accept that grape variety impacts wine and often choose a wine on the basis of grape variety. Why do we not apply our wine buying principles to food? · Having sorted out breed / variety, we can go on to think about feeding, husbandry and butchery.

|

A Longhorn cow – delicious!

Black and white job – not delicious! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What produce define Hampshire?

In France, different regions are defined by the food they produce, the wines (or other drinks) they make and by their cooking. Examples include: Normandy is known for its dairy products such as cheese and shell fish and cider; Gascony is known for all things duck and goose; Alsace for sauerkraut, charcuterie and tarts.

The sense of gastronomic identity is re-enforced by the Appellation Contrôlée system - or Appellation d'origine protégée (AOP) system as it is now.

The question posed is what produce define Hampshire? Or are there any produce that define Hampshire?

Before answering these questions, it can be noted that there are no Hampshire produce that have protected status – at any level. This, however, does not mean that there are no produce that do characterise Hampshire. I would site in particular:

Watercress Trout

In addition to these, whether or not they have protected status, there I would suggest that the following could be considered for local branding…

There are some produce that I have not included which look like prime candidates for inclusion in the list. The most obvious of these is wine. I have not included it because some of the wine growers, are simply grape farmers and sell their grapes to other wine producers to be made into wine. Conversely, some wine producers buy in grapes from other producers. I would not imply that all engage in this trade, but, without extensive research, it makes it difficult to have a judgement about branding.

I am sure there are many other candidates.

It would be nice if the authorities would start to promote Hampshire specific produce.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Does taste matter?

First, by “taste” I mean “flavour”!

One of the biggest surprises of being in Greece was that tomatoes tasted of (guess what?) tomatoes. Of course it should not have been a surprise but having been fed on a diet of flavourless tomatoes for so long I forgot what good tomatoes tasted like. I was reminded of a presentation given by the head tomato buyer for Sainsbury’s.

In the presentation she listed the buying criteria she uses for selecting tomatoes. They were something like:

· Long shelf life · Uniformly round · Consistent size · Red · Strong skins (to avoid bruising and breakage).

So, I asked, “what about flavour”. “No,” she said, “that does not matter.”

A similar tale unfolded (!) when I visited the Sparsholt College pig unit during an open day. They had a sign up showing 10 objectives for selecting pigs for breeding. I cannot remember them all but they were something like….

· Time to maturity · Health · Litter size · Minimum fat…..

Again no mention of flavour so I asked the guide why flavour does not appear on the list. I was told that it does not matter.

I am seriously of the view that flavour does matter – and there is research that shows this.

Flavour matters because…

· It stimulates the digestive juices which improves the digestion and enables us to absorb the nutrients better. · Good flavours encourage our appetites and entice us to eat healthily. · Food flavours give a feeling of pleasure and encourage us to enjoy the food. · Generally, good tastes draw us to good healthy food and bad tastes warn us about potential poisons.

These comments should persuade us to seek out and buy tasty wholesome produce rather than accepting bland flavourless food. There is, however, an irony.

Historically (when I was a boy) there was a general view that British meat had masses of flavour but French meat was generally tasteless. The result of the second half of this was that the French developed wonderful sauces to compensate for their tasteless meat; hence the reputation of French cooking.

Perhaps with the blandness of so many supermarket produce, our culinary skills will develop, rather than letting our taste buds be seduced by the artificial stimulants of sugar and salt.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Local food

It is that lovely time of year when fresh English asparagus is in season and in the shops. Curiously, however, the asparagus sold in Romsey’s one greengrocer was grown in Essex. I say “curiously” because it is rumoured that England’s largest asparagus grower is less than two miles from Romsey! Does it really matter that our asparagus has to be shipped 150 miles across the country? For several reasons I think it does…

1. It will never be as fresh as asparagus that is grown locally. 2. It can be assumed that there is a significant supply chain involved in getting the asparagus to Romsey – probably local distribution to a central market (Covent Garden), regional wholesaler, local wholesaler, distribution to shop. All these parties need to take a slice of the selling price, thus increasing what we have to pay. 3. This is most important – the local producer is isolated from the local community. This means that it would be difficult for him to attract local labour to pick the produce and he is forced to employ imported labour which might not be available after Brexit. If his produce were sold locally then maybe he could find local people to do the harvesting. I think that any argument that says that local pickers are not available, can be challenged because the John Lewis Partnership seems to have no problem attracting apple pickers at Leckford – indeed, it is difficult to get selected to help with the harvest. 4. Local produce is one of the things that defines a local region. The French have got this down to a tee. In and around Romsey there are produce that are recognisable as local (for example Test Valley trout), but the process could be taken further. This would benefit tourism and the community in general.

Having criticised the asparagus supply chain, there are worse! Garlic in Romsey shops mostly comes from Spain (not bad, but could be better) but some comes from China! Why? What possible reason is there for importing garlic from 5000 miles away – especially as some recent reports suggest that garlic from China is contaminated? When it is in season, surely the best solution is to buy garlic from the Isle of Weight or other local producers? |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

How can this be?

I recently bought a bottle of wine from a local supermarket. Pretty label; wire netting (presumably to keep something in); on special discount. The wine was Castillo La Paz, Tempranillo Syrah. That is not important. What is important is that it had two awards: Silver in 2015 from IWSC and Commended from Decanter. Incidentally, “Commended” means “also ran”. In addition it is recommended by The Guardian. Apart from awards and recommendations, also important is the quality of the wine.

Having opened the wine and poured a glass (an ISO tasting glass), I smelled the wine. I got a waft of red wine aromas (black fruit, chocolate etc) Good! However, after a second that was gone. In the mouth – nothing. No nasty cork tastes – absolutely nothing at all. The wine was not good. In fact it was very poor. Designed for people who do not like wine.

The question, then, is how come such a bad wine could receive two awards? Without making any aspersions, there could be several explanations:

1. The wine could have changed since 2015 when the awards were given. 2. When I tasted it, the wine might have been going through a closed period (probably related to the phase of the moon). 3. The organisations making the awards either employ people who have little sense of what is a good wine, or the tasters were under so much pressure to taste the quantity of wines needing assessment, that their sense of taste had been blown away. The British competition holder tasters each have to assess more wines than do the French competition tasters. 4. That the other wines in this wine’s category were so bad that this wine seemed really good. 5. That at the tasting the wine had been opened two days earlier and allowed to breath. 6. That IWSC and Decanter allowed commercial considerations to affect their assessment of the wine. After all they make money out of (1) having wines submitted for assessment and (2) by selling franchising material for wines that win awards. Would it be incredulous to ask whether a large supermarket would be a valued and special client for this organisation and would need to be treated specially? How could that be possible?

The lesson is, do not trust medal awards, particularly from British competition organisers, to guide you to good wines.

Prologue:

1. I looked up the wine on the retailers web site and got: Error 500. Sorry, we can't take you to that page at the moment Says it all really!

2. Another supermarket that sells the wine says: “Grown in Don Quixote's homeland, the old vines from Castillo La Paz thrive in red-brown sandy clay, rich in limestone and chalk. The clean and dry atmosphere creates optimum growing conditions for these ancient vines to produce wine of deep colour with concentrated berry flavours. A superb example of Tempranillo at its best.” And “21 out of 33 customers would recommend this product to a friend.”. I hope none of the 21 are friends of mine!

3. After leaving the bottle open for two days, the wine actually turned out quite nice. Reasonable amount of aroma and taste. Smooth and well rounded. Shame there were not instructions on the label saying “Open, leave standing for two days and then pour and drink.”

4. The producer does not even list the wine on his web site. Must be a special for the supermarket!

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Innovation or perfection

I got very excited when I recently read that plantings of Chilean Merlot had fallen by 20% over the past decade. Research suggests that this report is factually inaccurate but, in the true spirit of modern journalism, why let the facts get in the way of a good story?

The story did get me thinking about wine and fashion – particularly as so much of the wine industry is owned by the fashion industry.

There is a great temptation by wine producers to follow fashions and to produce wines that are in vogue. The problem is that the timescales of fashions and wine production are incompatible. A particular wine may be in fashion for 2 or 3 years. Wine timescales may be measured in generations – that can be the time for a vine to become fully productive of high quality grapes. There have over the years been reports of wine producers in less stringently controlled regions grubbing up less fashionable vine varieties and replacing them with the current fad. The problem is that, by the time the new vines become productive, the fashion has changed.

That said, there are changes that can be made fairly quickly – for example altering the amount of oak in a wine. Even doing this may not be possible or desirable. I am reminded of a Chablis producer who tried to sell us oaked Chablis. I asked why they produced oaked Chablis when the unoaked one was typical and delicious. I was told, “Because the English drink more oaked Chardonnay than any other wine.” (It was a few years ago.) The problem was that the oaked Chardonnay being drunk by the English was mass produced, usually in Australia and cost £5-7 a bottle and the oaked Chablis would have cost £12+ per bottle – and, because of the scale of production could never be less than that.

Given, then, that wine producers will have the greatest of difficulty chasing trends what can they do to stay in the market? Apart from spending buckets of money on marketing and brand building, the answer, I think, was illustrated to me when I went to a number of tastings from New World and Old World producers. When asked what were the main objectives of the producers the answers inevitably were: from the New World producers: “To innovate”; from the Old World producers: “To perfect our wines.”

Shame that perfection does not carry the same magic as innovation. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

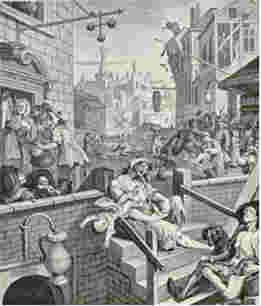

| Mother’s ruin

Before Christmas I heard a programme on the wireless about gin and its effect on society in the 18th century at the time of Hogarth’s famous Gin Lane picture. As I was listening to the appalling descriptions of affects of gin on family life, I started to reflect on the rise in popularity of gin at the current time. Why is a gin resurgence taking place? Just how much has the market for gin grown. Will it last?

Why it is happening has to be a matter of speculation. It could be due to a revival in cocktail drinking but that would not explain why gin now. After all, in the past few years there have been fads in tequila, vodka, whisky and beer. It could be that gin making is traditional in England – at least since it was brought over from Holland by William of Orange(?). It could be that dubbing down of big brand gins has opened up a window for artisan producers. If may be that, in a globalised drinks industry, we crave artisan products. It may be that barriers to entry are not too large – you do not need to be a very large operation to produce to a high value output.

The scale of growth of gin distillation in England seems substantial. The number of distilleries in England has grown from 23 in 2010 to 91 in 2015. It can be assumed that most of these are producing gin. At the end of 2015 England had only 18 less distilleries than Scotland. In 2010, England had only 30% of the number of distilleries in Scotland.

Although there is obviously growth in gin production in England, this must be put in the context that in the UK gin consumption is only 30% that of vodka, 25% that of Whisky and about the same as that of rum.

Now for the question of whether the gin revival will last. Firstly let me say that I enthusiastically welcome the growth in choice of gins – particularly the aspect of local. My suspicion however is that it is a fad that will diminish, probably in less than 5 years. Like so many of the good things in life, it is possible that the big companies will start to take over the new entrants and this could be followed by a rationalisation. As an alternative viewpoint (and this is an advantage of gin), we could see more and more innovations in the flavours of gin with, perhaps, more gins produced for specific types of cocktail. The possibilities are endless.

Perhaps everybody will become so depressed with the state of the world (I am not incidentally) that we shall return to Hogarth’s day and use gin as a release from everyday life! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What makes a menu stand out?

Whilst putting together the programme for the next few dinners my mind has been occupied in trying to understand what makes a really top class dinner menu. This has led me to study and, as a result, slobber over the menus from some of the top (3 Michelin star) restaurants in France. Just to put this into context, I was looking at menus costing from €150 to €450 per person – excluding wine.

The results are (I think) rather strange. Firstly, very few placed emphasis on top (priced?) ingredients such as foie gras, lobster, turbot and truffles. By and large, in reading the menus out of context, you would not know that they were coming from the world’s top eateries or that they would be so expensive. The establishments clearly are able to charge the amounts they do as a result of their reputations for continually and reliably serving up a perfect experience. I say experience because everything has to be perfect – the food, the wine, the service and the ambience.

I did notice that these restaurants use certain “themes” in their menus…

· Local food is a theme. Here the equivalent would be Romsonian lamb or trout. · Specific varieties of food get emphasised – even when the variety is not (in my view) the best – bœuf Charolais appears more than once amongst the top-tier restaurants. I would much rather eat Red Ruby, Hereford or Longhorn beef. · Surprise menus are not uncommon – you would have to have a lot of faith in the chef to spend €200 or more on the menu when you do not know what you are going to get! · Then there are multi-course gastronomic menus.

That said, I am still not sure I understand what is the perfect menu. Here I am going to break my rule of no questionnaires and ask you to let me know what you like to eat the most. Extensive piloting has shown that a simple question such as “What is your favourite food?” does not work. It generates responses such as “Depends on the circumstances.”, “Depends on the time of year.”, “Depends on my mood.” or “I like all food.” So I am going to ask you to play Dessert Island Dishes….

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||